Let’s pick up the Anglican/Episcopalian saga before looking at George Washington’s type of Christianity. As I said in the last entry we hear that the hero of our Revolution and our First President was Episcopalian and we think “he’s almost a Catholic!” but that only shows to go you how little we know about Episcopalians or Anglicans at the time of George Washington. This is an important topic for another reason as well. When we look at the question of Anglican’s having “Valid Orders” it is important that we know their history to see if their doctrines of Eucharist and Priesthood have always conformed to what we Catholics believe to be the historic faith of the Church as it has come to us from the Apostles.

|

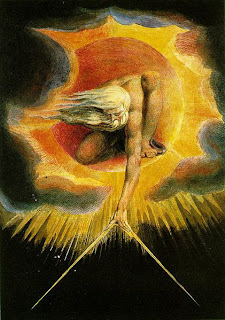

"Ancient of Days" by William Blake (1757-1827) British Poet and Painter, depicting God as the Architect of the Universe, a common theme in Enlightenment thought |

Henry VIII did not steer his Church of England on a Protestant course when he broke communion with Rome in 1536. He kept not only the Mass but virtually all Catholic doctrine and practice other than religious life. He closed the monasteries for a variety of reasons—financial gain for the crown being one of them but he changed almost nothing else. The Pope’s name was dropped from the Mass but the Mass remained otherwise unchanged even for the Latin. All Henry wanted was a non-papal Catholicism. But he obviously knew what the future held and the Council of Regency he appointed to govern England until his son and heir, the future Edward VI, was old enough to govern for himself, was decidedly Protestant in its religious views. Henry did die when his son was only nine and as Edward died before reaching his majority, this Regency Council governed England for the entire period. The Protestant leaning majority soon rid itself of the more conservative minority and under the aegis of Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury and thoroughly Protestant member of the Privy Council, transformed Henry’s non-papal Catholic Church into a Calvinist Church. As regards the sacraments and worship they did this in two steps. The first substantial Liturgical revision came with the 1549 Book of Common Prayer issued only two years after Edward’s ascension to the throne. (There had been a few interpolations of English into the communion rite of the Latin Mass almost immediately after Henry’s death, but the Mass itself was untouched for over two years while Archbishop Cranmer prepared his new liturgy) This first Prayerbook retained vestments, altars, and other Catholic ceremonial but it was no sooner published than Cranmer issued a second book that was stripped of almost all Catholic elements. Like Luther, Cranmer was particularly ardent to strip the Mass (and priesthood) of any sense of sacrifice. The rites of ordination of priests and consecration of bishops were similarly altered to remove any concept of a “sacrificing priesthood.” The motivation for this was the mistaken idea about Catholic teaching, an idea, incidentally, held by many Catholics who had exaggerated sound doctrine into superstitious claptrap that each Mass was in and of itself a “sacrifice” as opposed to the idea that in each Mass the one sacrifice of Christ becomes present to us. In orthodox Catholicism, unlike in what was once the popular Catholic imagination, Christ is not sacrificed again and again every time Mass is offered. Christ has died once and for all. In the Mass we are made present to that one eternal sacrifice which is sufficient for the redemption of the world.

The Mass neither repeats that sacrifice nor adds anything to it. Knowing this we can see why Cranmer, Luther and other Reformers were anxious to avoid the idea of the Mass as Sacrifice even if they over-reacted in their zeal to protect the uniqueness of Christ’s once-and-for-all sacrifice. But there were other problems in the Mass as well, The “offertory” prayers of the “old Mass” ambiguously suggested that there were two sacrifices at the Mass, the first and lesser being the sacrifice of bread and wine to God so that they could be used in the second and essential “sacrifice,” in which Christ’s one and eternal Sacrifice is made present (or in the exaggerated view, in which Christ is offered again (and again and again) in each Mass). Cranmer’s work of stripping the Mass of any idea of Sacrifice was quick but thorough. It reduced the Mass, now known as “Holy Communion” to a mere memorial of Christ’s saving death. Cranmer’s concept of Christ’s presence in the Eucharist was ambiguously confusing but is best summed up in the beautiful (but doctrinally problematic) prayer: Take and eat this in remembrance that Christ died for thee and feed on him in thy heart by faith and with thanksgiving. Beautiful sentiment—but is Christ present only by faith and what do we mean by remembrance?

In any event, At King Edward’s death in 1553, the Church of England had been thoroughly Protestantized and those clinging to Catholic theology or practice had been forced from their ecclesiastical offices and sometimes (but not always) imprisoned.

At Edward’s death, his Catholic sister Mary ascended the throne and in her five year reign restored the Catholic Faith and practice, bringing the Church of England back into the Roman Communion. Unfortunately she did this in a particularly violent and bloody way, without any modicum of restraint or prudence, despite the advice of her Catholic Archbishop of Canterbury (who was also her cousin) Cardinal Reginald Pole. Pole and Mary died the same day, November 17, 1558, leaving Mary’s successor, her Protestant half-sister Elizabeth, in need of a New Archbishop who could make a new—and Protestant--beginning.

Elizabeth was one of the few genuinely intelligent people to sit on the English throne and she was not only fluent in classical languages but well instructed in theology. (Curiously, while she had a keen grasp of doctrine it sometimes seems that she lacked Christian faith.) Her religious biases were for the sort of non-papal Catholicism of her Father. She liked ritual and well understood that religious ritual actually bolstered the authority of the Crown. But Elizabeth had a problem and that was getting the power to rule firmly into her hands. No one expected her to be Queen. They expected her to marry and her husband to be King. Elizabeth had no such strategy in mind. As she herself asserted, she had “the heart and stomach of a King” and was determined to rule in her own name. To consolidate her power she had to woo the House of Commons for its support against the at-the-time all-powerful House of Lords. The Commons, representing townsfolk, was thoroughly Protestant. Actually they were Puritans, staunch Protestants who wanted to rid the Church of England of anything Roman. The Reformation was on again and on with a fury. The communion tables came back, the altars went out. Vestments were destroyed; crosses and candles swept from the sanctuaries; statues and stained glass smashed. Ordinary table bread was used for Holy Communion and tankards replaced chalices. A new Prayerbook came out in 1559, substantially identical to the second Prayerbook of King Edward VI. Priests and bishops were married (though not to each other—that comes later.) Matthew Parker, her choice for Archbishop of Canterbury, was consecrated according to the Ritual as reformed by Cranmer during the time of King Edward, not according to the Catholic Rite. Theologians like Bishop John Jewel of Salisbury drew on Scripture and the Fathers to explain and justify the Reforms. Elizabethan Anglicanism differed from Rome but was very orthodox—though with a strong Calvinist bent—in its soteriology. Elizabethan Anglican sacramental theology is a bit more complex and while Catholics may not find it to be “orthodox,” was well rooted in patristics and sixteenth century New Testament scholarship. Elizabeth had a remarkably long reign—almost forty-five years—and by her death England was thoroughly Protestant and thoroughly Reformed (i.e. Calvinist). I don’t know that she was totally happy about that, but it is what she left as her legacy.

Elizabeth was succeeded by her Calvinist cousin, King James VI of Scotland who became James I of England. James too was highly educated and interested in matters theological. His wife, Anne of Denmark, was a convert from Lutheranism to Catholicism but James remained a staunch Anglican though of High-Church sentiments rather than Puritan. James is famous for having sponsored the English translation of the Bible that bears his name. Beginning in the reign of James I and continuing on through that of his son, Charles I, there was a spiritual and theological revival in the English Church that crystalized during the tenure of William Laud as Archbishop of Canterbury. Patristic scholarship and theological reflection, as well as somewhat of a recovery of the pre-Reformation English mystical tradition brought new—and very orthodox—life to the Church of England. Under Laud’s administration, there was also somewhat of a corresponding liturgical revival though by no means a restoration of pre-Reformation ceremonial. Unfortunately, it came crashing down with executions of King Charles and Archbishop Laud in 1649 and 1645 respectively. During Oliver Cromwell’s Puritan Commonwealth the Church of England splintered hopelessly. The Episcopacy was abolished (temporarily) in favor of Presbyterianism but religious dissent burst out into numerous exotic forms with Quakers and Levelers, Baptists and Diggers, Congregationalists, Ranters and Fifth Monarchists. What was beneath this disintegration of a National Church into numerous sects of dubious orthodoxy was the triumph of a neo-gnostic Illuminism in which the subjective religious experience of the individual was allowed to take precedence over the collective wisdom and ancient tradition of the community of the faithful. When ultimate authority is not some outside source—be it scripture, sacred authors, papal authority, tradition—but individual opinion then there is no cohesive religious bond that means anything. Reason may—or may not—play a role in the formation of opinions and while most of these sects were radically subjective with no regard for reason, there were many in society that saw religion as essentially irrational and opted not for faith but instead for rational philosophy and natural science to replace any sort of Divine Revelation be it canonical or individual. This then, the mid-seventeenth century, is a period in which many embraced Enlightenment rationalism leading them to a very rational view of God as the impersonal architect of the universe. It is here that we get Issac Newton, John Locke, Adam Smith, Alexander Pope, Joseph Priestly and a host of other very modern thinkers who had moved far beyond a theocentric view of science, philosophy, human society, religion, and the universe itself. This was also the incubator in which Freemasonry was hatched as a rational alternative to Christian myth and ritual. This rationalism was not without its effect on the Church of England which was closely connected to the universities and whose clergy were trained at those universities. In the late seventeenth and throughout the eighteenth centuries there were many priests and bishops—not to mention laity—who conformed in worship to Anglican practice but whose theology was riddled with rationalism that led to Arianism, Socinianism, and even Unitarianism. Christ’s Virgin Birth and his Physical Resurrection were called into question by some and many saw the Church existing primarily for character formation in sound morals rather than as a belief system. Sermons were often moral exhortations free of specifically Christian doctrine and prayers were no more than the formation of moral precepts with references to a Transcendent Being. This skepticism was by no means limited to Anglicanism and in America was found also among the New England Congregationalists. It would cause a reaction in the formation of an Evangelical wing that was behind the First Great Awakening with the preaching of such Anglican promoters of Christian orthodoxy as George Whitefield and John Wesley. In the nineteenth century it would be responsible for the reaction we call The Oxford Movement and the revival of Catholic heritage in the Church of England and the American Episcopal Church. At the time of the American Revolution, however, the Anglican and Episcopal Churches had an evangelical wing but were heavily tipped in favor of religious rationalism. But what about George himself? Did he hold an evangelical faith or was he given to religious rationalism? Well that is for next time.